Picture this: you’re moving into your first apartment, wrestling a massive couch through a narrow hallway. You reach the corner where the corridor turns 90 degrees, and suddenly you’re stuck. No matter how you twist, turn, or sweet-talk that piece of furniture, it just won’t budge around the bend.

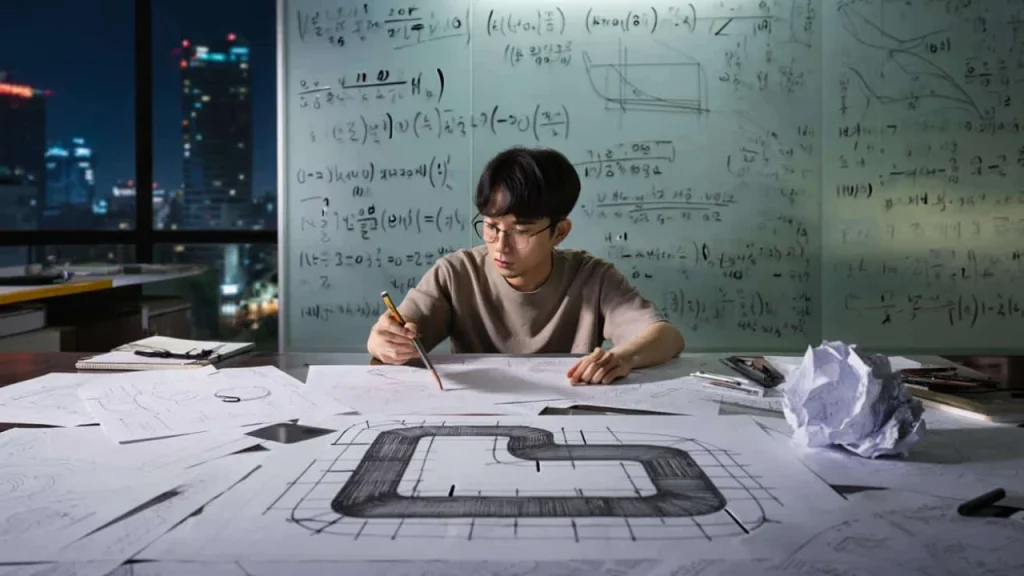

What started as a weekend nightmare for countless renters became one of mathematics’ most enduring puzzles. And after nearly 60 years of stumping brilliant minds across the globe, a quiet 31-year-old from South Korea has finally cracked it.

The story isn’t just about furniture or geometry. It’s about how the most innocent questions can evolve into legendary challenges that define entire careers—and how sometimes, the biggest breakthroughs come from the most unexpected places.

When Moving Day Became Mathematical Legend

Back in 1966, mathematician Leo Moser posed what seemed like a perfectly reasonable question. Imagine an L-shaped corridor, each arm exactly one meter wide. What’s the largest rigid, flat shape you could maneuver around that right-angled corner without lifting, bending, or breaking it?

This deceptively simple puzzle became known as the moving sofa problem, and it quickly transformed from a casual geometric curiosity into one of the field’s most notorious unsolved mysteries.

The challenge sounds straightforward: maximize the area of a shape that can squeeze through that corner turn. But as decades of frustrated mathematicians would discover, finding the perfect sofa proved far more complex than anyone imagined.

“What makes this problem so captivating is how it bridges pure mathematics with something everyone can visualize,” explains Dr. Sarah Chen, a geometry professor at MIT who has studied the problem extensively. “Every person who’s ever moved furniture understands the basic challenge.”

Early attempts produced increasingly creative solutions. In 1968, John Hammersley designed a shape with an area of about 2.2074 square meters—significantly larger than any simple rectangle or circle could achieve. Then in 1992, Joseph Gerver pushed the boundaries even further with an intricate, multi-curved design reaching approximately 2.2195 square meters.

For over three decades, Gerver’s bizarre, serpentine sofa held the crown as the largest known solution. Computer simulations suggested no bigger shape should fit, but simulations can only test specific designs and approximations. They couldn’t provide the mathematical certainty that no larger sofa exists anywhere in the realm of possibility.

The Breakthrough That Changed Everything

The turning point came from the most unlikely source: South Korea’s mandatory military service. While completing his conscription at the National Institute for Mathematical Sciences, young mathematician Baek Jin-eon encountered the moving sofa problem for the first time.

What drew Baek to this particular puzzle wasn’t just its fame, but its mysterious nature. Unlike other mathematical challenges with established frameworks and clear approaches, the moving sofa problem remained frustratingly vague—just an awkward question drifting through academic circles since the 1960s.

Baek’s approach differed fundamentally from his predecessors. Instead of trying to design better sofas, he focused on proving mathematical limits. Using advanced calculus techniques and geometric optimization theory, he demonstrated that Gerver’s 1992 design represents the absolute maximum possible area.

The key details of Baek’s achievement include:

- Proof that no sofa can exceed 2.2195 square meters in area

- Confirmation that Gerver’s 1992 design is mathematically optimal

- Development of new theoretical frameworks for similar geometric problems

- Resolution of a 58-year-old mathematical mystery

“Baek’s work is remarkable because he didn’t just find a better solution—he proved definitively that no better solution exists,” notes Dr. Michael Rodriguez, a computational geometry expert at Stanford University. “That’s the holy grail in mathematics: not just finding answers, but proving they’re the best possible answers.”

| Year | Mathematician | Sofa Area (sq meters) | Achievement |

| 1966 | Leo Moser | N/A | First posed the problem |

| 1968 | John Hammersley | 2.2074 | First major improvement |

| 1992 | Joseph Gerver | 2.2195 | Best known solution |

| 2024 | Baek Jin-eon | 2.2195 | Proved optimal limit |

Why This Discovery Matters Beyond Moving Day

While the moving sofa problem might sound like an abstract exercise, Baek’s breakthrough has implications reaching far beyond geometry classrooms. The mathematical techniques he developed could revolutionize how we approach optimization problems in robotics, urban planning, and industrial design.

Consider autonomous vehicles navigating tight spaces, or robotic arms maneuvering through complex environments. The same mathematical principles that determine optimal sofa shapes could help engineers design more efficient pathfinding algorithms for robots operating in constrained spaces.

Manufacturing industries face similar challenges when designing products that must fit through specific openings during production or assembly. Baek’s optimization methods could streamline these processes, reducing waste and improving efficiency.

“This isn’t just about theoretical mathematics,” emphasizes Dr. Lisa Thompson, a robotics researcher at Carnegie Mellon. “These optimization principles have direct applications in how we design smart systems that interact with physical spaces.”

The techniques also apply to space mission planning, where every cubic centimeter matters. Spacecraft components must fit through launch vehicle fairings while maximizing functionality—a challenge remarkably similar to the moving sofa problem.

Even city planners could benefit from Baek’s work. When designing intersections, parking structures, or emergency vehicle access routes, understanding optimal geometric configurations becomes crucial for public safety and traffic efficiency.

The broader mathematical community has already begun exploring how Baek’s approach might tackle other long-standing geometric puzzles. Problems involving optimal packing, shape optimization, and constrained movement could all benefit from similar analytical frameworks.

FAQs

What exactly is the moving sofa problem?

It’s a geometry puzzle asking for the largest flat shape that can be moved around a 90-degree corner in an L-shaped corridor where each arm is one meter wide.

How did Baek Jin-eon solve it?

Instead of designing new sofa shapes, he used advanced mathematical techniques to prove that Joseph Gerver’s 1992 design represents the absolute maximum possible area.

Why did it take 58 years to solve?

The problem required proving that no better solution exists anywhere, which is much harder than just finding good solutions. This type of mathematical certainty demands sophisticated theoretical frameworks that took decades to develop.

What’s the optimal sofa area?

The maximum possible area is approximately 2.2195 square meters, achieved by Gerver’s complex curved design from 1992.

Does this have real-world applications?

Yes, the optimization techniques could improve robotics, manufacturing, space mission planning, and any field involving efficient movement through constrained spaces.

Are there other unsolved problems like this?

Many similar geometric optimization puzzles remain unsolved, and mathematicians are already exploring how Baek’s methods might apply to other long-standing challenges.