Sarah was 32 when she first heard the term “maternal microchimerism” from her doctor. She’d been struggling with an autoimmune condition for years, and during one appointment, her physician mentioned something that stopped her cold: “You know, you still carry some of your mother’s cells inside you.”

Sarah stared at him, confused. Her mother had passed away five years earlier. “What do you mean?” she asked.

“Well,” the doctor explained gently, “during pregnancy, mothers don’t just pass genes to their children. Some of their actual cells cross over and stay in the baby’s body for life. You literally have a piece of your mom still with you.”

The Secret Life of Cells That Travel Between Generations

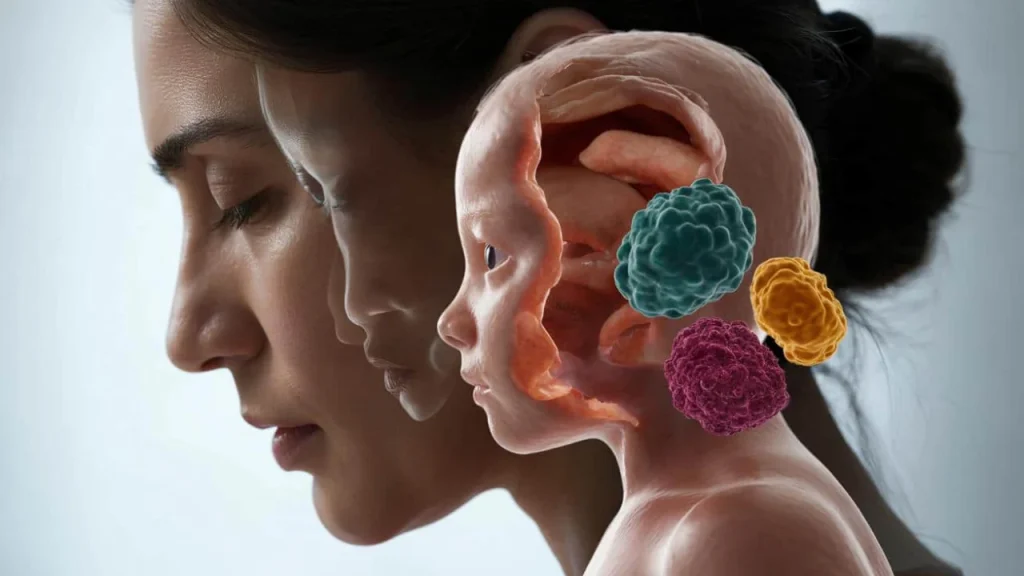

What Sarah learned that day reveals one of biology’s most fascinating mysteries. Maternal microchimerism is the scientific term for this incredible phenomenon where a mother’s cells migrate into her developing baby and remain there for decades—sometimes for an entire lifetime.

Think about it: long after the umbilical cord is cut and a child grows up, moves away, and starts their own life, their mother’s cells are still quietly working inside their organs. These cellular hitchhikers have been found in the liver, heart, skin, and even the brain of adult children.

“What’s remarkable is that these cells are incredibly rare—sometimes just one in a million—yet they manage to survive and potentially influence health throughout a person’s life,” explains Dr. Jennifer Martinez, a reproductive immunologist at Stanford University.

The discovery isn’t new, but scientists are still unraveling its implications. Researchers first noticed this cellular mixing in the 1960s when they found cells with maternal genetic signatures inside children long after birth. What they didn’t expect was learning that the traffic flows both ways—fetal cells also cross into mothers and can persist for decades.

Where Mom’s Cells Hide and What They Do

These maternal cells don’t just randomly float around your body. They seem to have specific destinations and purposes, though scientists are still piecing together the full picture.

Here’s what research has revealed about where these cells settle and their potential roles:

| Location in Body | Potential Function | Research Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Liver | Tissue repair and regeneration | Often found near damaged areas |

| Heart | Cardiac muscle support | May help with heart disease recovery |

| Brain | Neural protection | Found in regions affected by Alzheimer’s |

| Skin | Wound healing | Appear at injury sites |

| Bone marrow | Blood cell production | May influence immune responses |

The behavior of these cells tells a fascinating story. In many cases, they appear to act like a biological emergency response team. When tissues are damaged or stressed, maternal cells often show up at the scene, suggesting they might help with repair and healing.

“We’ve observed maternal cells clustering around areas of tissue damage, almost like they’re responding to distress signals,” notes Dr. Robert Chen, a cellular biologist at Harvard Medical School. “It’s as if they’re still trying to protect and heal their child, even decades later.”

But the story isn’t entirely positive. Some research links maternal microchimerism to autoimmune diseases, where the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues. The presence of foreign cells might sometimes confuse the immune system, leading it to overreact.

The Immune System’s Surprising Tolerance

Here’s what makes maternal microchimerism truly puzzling from a scientific standpoint: these cells should be rejected immediately. Your immune system is designed to recognize “self” versus “foreign” and eliminate anything that doesn’t belong—from viruses to transplanted organs.

Maternal cells carry a completely different genetic profile, so theoretically, they should be destroyed like a mismatched organ transplant. Yet somehow, they not only survive but thrive for decades.

Recent research is beginning to solve this mystery. A groundbreaking study published in the journal Immunity found that specific maternal immune cells act like biological teachers, training the child’s immune system to tolerate their presence.

- These “teacher cells” display special proteins that signal “friend, not foe”

- They educate the child’s immune cells about what should and shouldn’t be attacked

- This training creates a lasting tolerance that protects maternal cells from destruction

- The process begins in the womb and continues after birth

“It’s like the maternal cells are carrying a diplomatic passport,” explains Dr. Lisa Thompson, an immunologist at Johns Hopkins. “They’ve negotiated safe passage and established permanent residency.”

What This Means for Your Health

Understanding maternal microchimerism could revolutionize how we think about health, disease, and even personalized medicine. The implications reach far beyond simple biological curiosity.

For autoimmune diseases, this research offers new hope. If scientists can figure out how maternal cells sometimes trigger immune problems, they might be able to prevent or treat conditions like lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis.

Cancer research is another promising area. Some studies suggest that maternal cells might help fight tumors, while others indicate they could potentially contribute to cancer development. The key is understanding when these cells help and when they harm.

“We’re looking at maternal microchimerism as a potential therapeutic tool,” says Dr. Amanda Rodriguez, an oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering. “If we can harness these cells’ natural healing abilities, we might develop new treatments for various diseases.”

The psychological impact shouldn’t be overlooked either. For many people, learning about maternal microchimerism provides comfort, especially those who have lost their mothers. There’s something profoundly moving about knowing that a part of your mother remains with you, literally and forever.

Reproductive medicine is also being transformed by this knowledge. Understanding how cells cross between mother and baby during pregnancy could lead to better ways to prevent complications and ensure healthy outcomes.

Future research will likely focus on:

- Identifying which maternal cells are beneficial versus harmful

- Developing ways to enhance positive effects while minimizing negative ones

- Creating new therapies based on maternal cell biology

- Understanding how this phenomenon varies between different populations

As science continues to unravel the mysteries of maternal microchimerism, one thing becomes clear: the bond between mother and child runs deeper than anyone previously imagined. It’s not just emotional or psychological—it’s cellular, lasting, and literally life-changing.

FAQs

Do all people have maternal cells inside them?

Most people do, but the number and location of maternal cells varies significantly between individuals.

Can these maternal cells cause health problems?

Sometimes yes, sometimes no. They may contribute to autoimmune diseases in some people while helping with tissue repair in others.

Do fathers’ cells also stay in children?

No, only maternal cells cross the placenta during pregnancy. Paternal cells don’t have this ability.

How long do maternal cells survive in the body?

Some maternal cells have been found in people well into their 60s and beyond, suggesting they can persist for an entire lifetime.

Can maternal cells be removed from the body?

Currently, there’s no practical way to selectively remove maternal cells, and it’s unclear whether doing so would be beneficial or harmful.

Does this happen in all pregnancies?

Yes, maternal microchimerism appears to occur in virtually all pregnancies, though the extent varies from case to case.