Sarah Martinez still remembers the day her oncologist delivered the crushing news. After six months of checkpoint inhibitor therapy, her cancer hadn’t budged. “It’s like your immune system just can’t see the tumor,” the doctor explained gently. “Sometimes cancer cells are simply too good at hiding.”

That conversation happened three years ago, and Sarah isn’t alone. Despite revolutionary advances in cancer immunotherapy, roughly 70% of patients with certain cancer types see little to no response from current treatments. Their tumors have mastered the art of invisibility, slipping past immune defenses like skilled camouflage artists.

But now, researchers in China believe they’ve found a way to tear away that cloak of invisibility using something unexpected: our body’s memory of old viral infections.

Why Current Cancer Immunotherapy Hits a Wall

Modern cancer immunotherapy seemed like the holy grail when it first emerged. Drugs called checkpoint inhibitors work by releasing the brakes on T cells, essentially giving your immune system permission to attack cancer. These treatments have saved countless lives, transforming terminal diagnoses into manageable conditions for many patients.

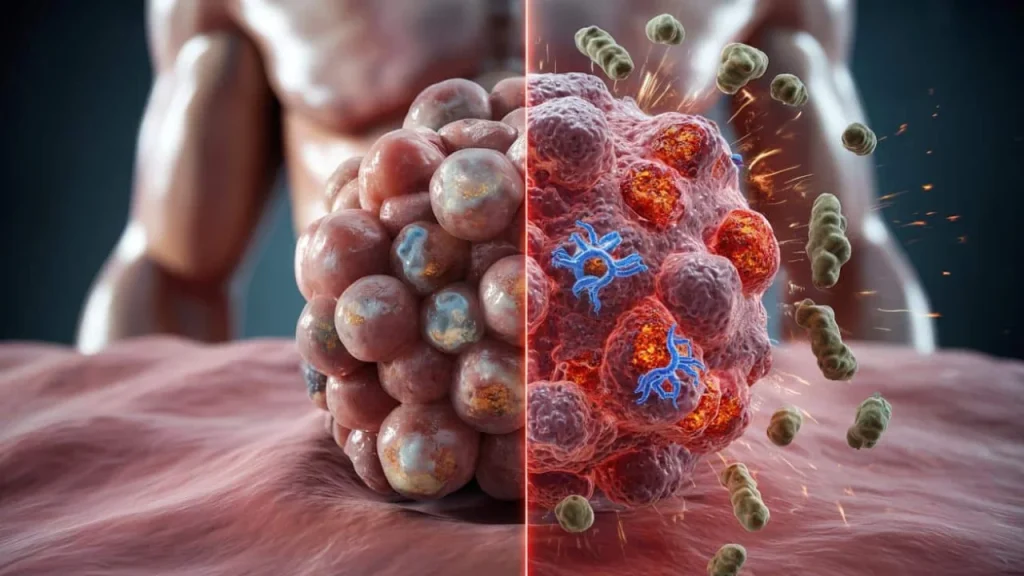

Yet there’s a massive blind spot. Some cancers produce what scientists call “cold tumors” – malignant masses that barely register as threats to the immune system.

“The problem is these tumors don’t carry enough mutations to look foreign,” explains Dr. James Chen, an immunologist not involved in the research. “They generate very few abnormal proteins that would normally flag them as dangerous.”

Without these warning signals, cancer cells continue growing in plain sight. Even worse, they often produce high levels of PD-L1, a protein that actively shuts down nearby immune cells. It’s like having a security guard who not only can’t spot intruders but also tells other guards to look the other way.

Turning Viral Memory Into Cancer-Fighting Power

The breakthrough comes from researchers at Shenzhen Bay Laboratory and Peking University, who decided to approach the problem from a completely different angle. Instead of trying to make tumors more visible, they asked: what if we could recruit the immune cells we already have?

Your body carries an army of memory T cells from every viral infection you’ve ever fought – chickenpox, common colds, flu strains, and more. These cells are battle-tested, numerous, and ready to spring into action at a moment’s notice.

The team developed a synthetic compound called iVAC (intratumoral vaccination chimera) that performs two crucial functions simultaneously:

- Strips away PD-L1 proteins that suppress immune responses

- Forces cancer cells to display viral fragments on their surface

- Activates memory T cells that recognize these viral signatures

- Transforms “cold” tumors into “hot” immune targets

“We’re essentially tricking the immune system into thinking cancer cells are infected with viruses,” notes Dr. Maria Rodriguez, a cancer researcher reviewing the study. “The body’s antiviral response is incredibly powerful – we’re just redirecting it.”

| Traditional Approach | New iVAC Strategy |

|---|---|

| Relies on tumor-specific antigens | Uses viral memory from past infections |

| Works for 20-30% of patients | Targets broader patient population |

| Requires recognizable tumor markers | Creates artificial viral signatures |

| Limited by tumor mutation levels | Leverages existing immune memory |

The iVAC treatment is injected directly into tumors, where it gets to work immediately. Using bioorthogonal chemistry – reactions that can safely occur inside living tissue – the compound targets PD-L1 proteins and breaks them down from within cancer cells.

What This Could Mean for Patients

The implications extend far beyond the laboratory. For patients like Sarah, whose tumors proved resistant to conventional immunotherapy, this approach could offer new hope.

Initial testing in mouse models showed remarkable results. Tumors that previously ignored immune attacks suddenly became vulnerable. Memory T cells that had been sitting idle for years or decades sprang into action, treating cancer cells like familiar viral enemies.

“The beauty of this approach is that it doesn’t require finding rare cancer-specific targets,” explains Dr. Lisa Thompson, an oncologist specializing in immunotherapy. “Almost everyone has memory cells against common viruses like CMV or varicella.”

The strategy could be particularly valuable for cancers that currently have limited treatment options:

- Pancreatic cancer, known for immune evasion

- Certain types of brain tumors

- Liver cancers with low mutation rates

- Some forms of ovarian cancer

Unlike systemic treatments that affect the entire body, iVAC works locally within tumors. This targeted approach could reduce side effects while maximizing immune activation where it’s needed most.

The treatment also shows promise for combination therapies. Researchers believe iVAC could work alongside existing checkpoint inhibitors, creating a one-two punch that first makes tumors visible and then releases immune brakes simultaneously.

The Road to Human Trials

While the research is promising, several hurdles remain before this treatment reaches patients. Safety testing must confirm that redirecting antiviral responses doesn’t cause harmful autoimmune reactions.

Scientists also need to determine optimal dosing, timing, and which viral signatures work best against different cancer types. The complexity of human immune systems means results may vary significantly between individuals.

“We’re still in early stages, but the principle is sound,” cautions Dr. Rodriguez. “Using our body’s existing immune memory is an elegant solution to a complex problem.”

For patients currently battling treatment-resistant cancers, this research represents something invaluable: hope that science continues pushing boundaries. While Sarah’s tumor eventually responded to a different experimental therapy, millions of others still wait for breakthrough treatments that could turn the tide in their fight.

The war against cancer has taught us that progress often comes from unexpected directions. By looking backward to our immune system’s memory, researchers may have found a way to see forward to more effective treatments.

FAQs

What makes some tumors “invisible” to the immune system?

These tumors have few genetic mutations, so they produce very few abnormal proteins that would normally flag them as threats to immune cells.

How does the iVAC treatment work?

It forces cancer cells to display viral fragments on their surface while removing immune-suppressing proteins, making tumors look like viral infections to the immune system.

Is this treatment available for patients now?

No, the research is still in laboratory stages and requires extensive safety testing before human trials can begin.

Which cancers might benefit most from this approach?

Pancreatic, brain, liver, and ovarian cancers that typically resist current immunotherapy treatments could be primary targets.

Are there risks to redirecting antiviral immune responses?

Researchers must carefully study whether this approach could trigger harmful autoimmune reactions before moving to human testing.

Could this work alongside existing cancer treatments?

Yes, scientists believe iVAC could enhance current checkpoint inhibitor therapies by making tumors more visible to the immune system first.